To understand the great crisis that was generated in Chile in the early 1970s and that culminated with the military intervention led by General Augusto Pinochet and the suicide of Salvador Allende, it is necessary to know the facts that preceded this stage of our history.

In September 1973, Salvador Allende died. Three years before he was elected President of Chile, after four attempts.

In 1952 he suffered a wide defeat against Carlos Ibañez. In 1958 he almost succeeded and was barely 33,000 votes away from victory. In 1964 Eduardo Frei Montalva defeated him by 432,000 votes.

For this reason, in the 1970 campaign there were many skeptics, they distrusted the left itself, they were not sure if it would be able to win in another attempt to reach the presidency.

Finally, and on the condition that he govern together with the leaders of the popular unity parties, the left parties supported his candidacy. It would be a president without autonomy of command.

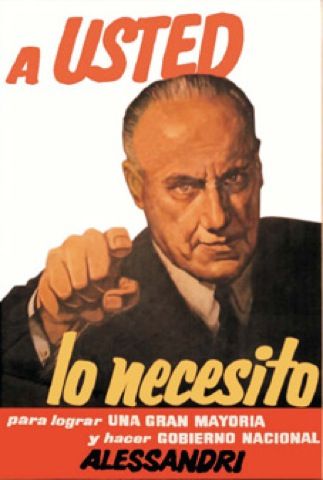

His opponents in 1970 were former president Jorge Alessandri, representing the right-wing sector, although he personally rejected being branded a rightist or conservative, preferring to be associated with efficiency and accuracy. In the campaign his austerity features would stand out, for fifteen years he lived alone in an old building near the Plaza de Armas in Santiago. What could play against him would be his advanced age, since he would enter La Moneda at 78 years old.

The other rival was Radomiro Tomic, standard-bearer of the Christian Democrats. His slogan was "not a step back" in the conquests achieved with Frei, President in those days. With two candidates as opposed as Alessandri and Allende, the electorate was polarizing. Tomic offered a program similar to Allende's although he warned that changes would be made in freedom and democracy.

Allende was a skillful candidate, he never presented himself as a Marxist, who if he succeeded would implant Marxism and the dictatorship of the proletariat. And the night of the triumph he would repeat: "My government will not be a communist, socialist, or radical government; it will be the government of the forces that make up the Popular Unity..."

Allende's program consisted of two parts, one was "The First 40 Measures." Forty promises offered to the people: Half a liter of milk for each child, schoolchildren would spend the summer at the presidential house in Viña del Mar, books and school supplies would be free, no one would pay in hospitals, homes that were not mansions would be exempt from contributions (house tax), all people over 60 years old would have retirement even if they did not have social security. History would show that many of these promises are difficult to fulfill, but the educational level of a large part of the Chileans of those times was quite precarious.

Other measures contemplated the nationalization of the large copper and iron mining companies, banks, the telephone company, foreign trade, and large monopolistic companies. He listed them as 45. But he warned: "All these expropriations will always be carried out with full protection of the small shareholder; we are not going to strip anyone."

Allende in the human sense: "In thirty-two years as a politician they have told me everything, except that I have stolen or that I am homosexual."

|

| Allende and his relation with the Communist Party |

Regarding the Communist Party being able to dominate it, its old disputes with the community were remembered. In 1948 he commented before the Senate that the Chilean socialists who recognized many of the achievements of Soviet Russia, rejected its political organization and many laws that restricted individual freedoms... In fact, since those times the Socialist Party had been leaning towards the extreme left.

The triumph of an Allende who declared himself a Marxist, but who affirmed that he would make a democratic government could be accepted by a rather tolerant Chilean.

The Diario Ilustrado (of a conservative tendency) published before the elections: "There is no doubt that we do not want for Chile what the Popular Front brought to Spain: burned temples, desecrated convents, raped nuns."

With this climate the presidential elections of September 4th, 1970 took place.

Allende triumphed at the polls with 1,075,616 votes (36.3%). Second was Jorge Alessandri with 1,036,278 votes (34.9%) and third, Tomic with 824,849 votes (27.8%).

Allende was the virtual winner although with a very narrow first relative majority. He beat Alessandri by just 39,000 votes (1.4%).

The result also revealed that almost 2/3 of the electorate rejected a Marxist alternative. Those who voted for Alessandri and Tomic (2 out of 3 Chileans) believed in democracy.

The electoral process had not yet finished, the Chilean Constitution established that the citizen who obtained half +1 of the votes was anointed as President-elect. Allende lacked a lot: 400,000 votes (15.2%).

When there is no such majority, the Constitution indicates the way: the full Congress (50 Senators and 150 deputies) will have to choose between the first two majorities. In this case, it had to be between Allende and Alessandri.

Both arrived before the full Congress on equal terms. The Christian Democrats during the electoral campaign had proposed creating the second round, as in France. In this way, the elected President would represent the great majorities. However, neither the supporters of Alessandri nor those of Allende accepted this initiative.

|

| Jorge Alessandri Rodriguez - President of Chile (1958-1964) |

Hence, the transcendental responsibility of settling the lawsuit remained with Congress.

There was a tradition that was very heavy for Chileans. Until then, the full Congress had always respected the first majority. Even during the campaign the three candidates repeated "whoever wins by one vote will be the president."

Now came the dramatic dilemma. Those who voted for Alessandri argued: it is true that this betrayal exists, but it was between democratic candidates; now it is to open the doors of La Moneda (government palace) to Marxism, being a minority.

In the full Congress Allende was also a minority. It had only 78 parliamentarians. Much less than half. If Allende expected to be President, he must necessarily knock on the doors of the Christian Democracy. This party with its 75 parliamentarians decided.

But the Popular Unity aroused misgivings. Allende was accompanied by some undesirable characters. Who could guarantee that the same thing that happened with Fidel Castro, who in Sierra Maestra proclaimed himself a democrat, catholic and devotee of the Virgin, would not happen to him?

In a dramatic meeting, the National Board of Christian Democracy agreed with its parliamentarians that they would give Allende a vote in full Congress, but provided that they accept compliance with 7 Statutes of Democratic Guarantees, which would be incorporated into the Constitution.

The 7 guarantees were:

- The Constitution ensured the free creation, existence and development of political parties

- Free access to the press, radio and television of all streams under equal conditions.

- It was constitutionally enshrined that the public force would be composed exclusively of the Armed Forces and Police, and that neither popular militias nor guards could be organized.

- The Armed Forces and Carabineros (Chilean police) would be professionalized, hierarchical, obedient and non-deliberative institutions. Full power was reserved to the Commanders in Chief for the appointment of their subordinates.

- In the Statute of Education it was proclaimed that it would be independent of any official ideological orientation.

- The constitutional guarantee that establishes the right to associate, through cooperatives or unions, and that the right to strike would be maintained.

- The constitutional guarantees of the right of assembly and personal freedom were modernized.

For the first time distrust was manifested towards who would be elected President of the Republic.

The full Congress finally elected Allende President of Chile with 2 thirds of the parliamentarians: 153 votes against 35 for Alessandri and 7 blank. This is how the Christian Democrats allowed Allende to reach the presidency of Chile.

* Information based mainly on the work by Hernan Millas and Emilio Filippi "Anatomy of a Failure".

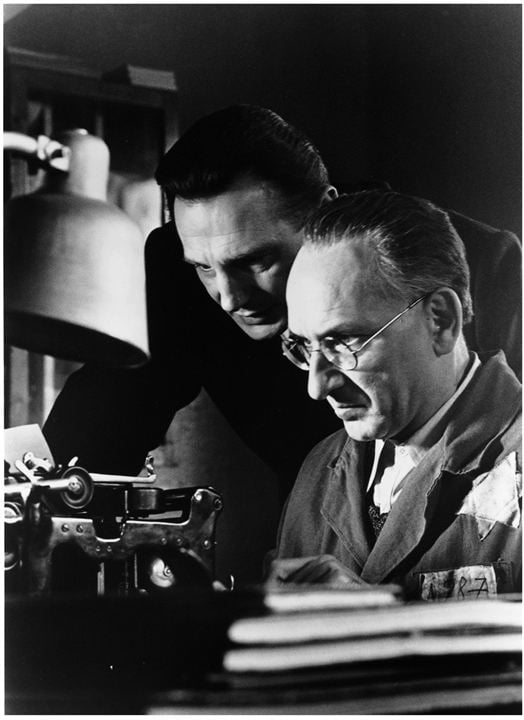

Hernán Millas was born on May 5th, 1921, and studied Law for a year at the University of Chile, and later devoted himself to journalism. He worked as a reporter and columnist in the newspapers El Clarín and La Época, in the "Ercilla" and "Hoy" magazines, and on the Santiago radio. He also wrote several books. And in 1985 he received the National Prize for Journalism.

Emilio Filippi, University Professor received the National Journalism Award in 1972 with a mention in writing. He began his life in journalism in 1942 working for the newspaper "La voz de la columna" in Villa Alemana, of which he became its director. In 1965, he joined as Zig-Zag's newspaper publishing manager.

He was director of the magazine "Ercilla" between 1968 and 1976. He was the founder and director of the magazine “Hoy” and of the newspaper "La Época'' (1987), which he directed until 1993. Same year that he was ambassador of Chile in Portugal, appointed by President Patricio Aylwin.