Para comprender la gran crisis que se genero en Chile a principios de los años 1970 y que culmino con la intervención militar encabezada por el General Augusto Pinochet y el suicidio de Salvador Allende, es necesario conocer los hechos que antecedieron esta etapa de nuestra historia.

En Septiembre de 1973, Salvador Allende murió. Tres años antes era elegido Presidente de Chile, luego de cuatro intentos.

En 1952 sufrió una amplia derrota en contra de Carlos Ibañez. En 1958 casi lo consiguió y estuvo apenas a 33.000 votos de la victoria. En 1964 Eduardo Frei Montalva lo derroto por 432.000 votos.

Por eso, en la campaña de 1970 hubo muchos escépticos, desconfiaban en la misma izquierda, no estaban seguros si seria capaz de ganar en otro intento por llegar a la presidencia.

Finalmente y con la condición que gobernara junto a los jefes de partidos de la unidad popular, los partidos de izquierda apoyaron su candidatura. Seria un mandatario sin autonomía de mando.

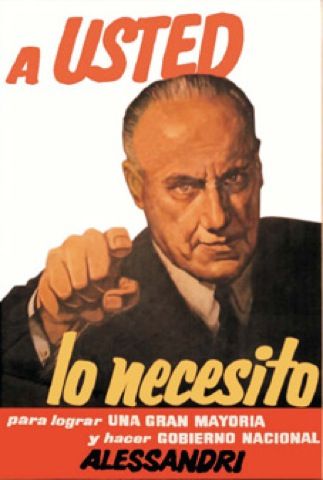

Sus oponentes en 1970, eran el ex presidente Jorge Alessandri, representando al sector de la derecha, aunque él personalmente rechazaba que lo tildaran de derechista o conservador, prefería que lo asociaran con la eficiencia y la exactitud. En la campaña se destacarían sus rasgos de austeridad, hacia quince años que vivía solo en un antiguo edificio cercano a la Plaza de Armas de Santiago. Lo que podia jugarle en contra seria su avanzada edad, ya que entraría a La Moneda a los 78 años.

El otro rival era Radomiro Tomic, abanderado de la Democracia Cristiana. Su slogan era "ni un paso atrás" en las conquistas logradas con Frei, Presidente en esos días. Con dos candidatos tan opuestos como Alessandri y Allende, el electorado fue polarizándose. Tomic ofrecía un programa similar al de Allende aunque advertía que se harían los cambios en libertad y democracia.

Allende fue un candidato hábil, nunca se presento como marxista, que de triunfar implantaría el marxismo y la dictadura del proletariado. Y la noche del triunfo repetiría: Mi gobierno no sera un gobierno comunista, ni socialista, ni radical; sera el gobierno de las fuerzas que componen la Unidad Popular..."

El programa de Allende constaba de dos partes, una eran "Las Primeras 40 Medidas". Cuarenta promesas que ofrecía al pueblo: Medio litro de leche para cada niño, los escolares veranearían en la casa presidencial de Viña del Mar, los libros y utiles escolares serian gratuitos, nadie pagaría en los hospitales, las viviendas que no fuesen mansiones estarían exentas de contribuciones, todas las personas mayores de 60 años tendrían jubilación aunque no tuviesen prevision social. La historia demostraría que muchas de esas promesas son difíciles de cumplir, pero el nivel educacional de gran parte de los chilenos de esos tiempos, era bastante precario.

Otras medidas contemplaban la nacionalización de la gran minería del cobre y del hierro, los bancos, la compañía de teléfonos, el comercio exterior, las grandes empresas monopólicas. Las enumeraba serian 45. Pero advertía: "Todas estas expropiaciones se harán siempre con pleno resguardo del pequeño accionista; no vamos a despojar a nadie".

Allende en lo humano convencía: "En treinta y dos años de politico me han dicho de todo, menos que he robado o que soy homosexual".

|

| Allende y su relación con el Partido Comunista |

Respecto a que el Partido Comunista pudiera dominarlo se recordaban sus viejas disputas con la colectividad. En 1948 comentaba ante el Senado, que los socialistas chilenos que reconocían muchos de los logros de la Rusia Soviética, rechazaban su organización política y muchas leyes que coartaban las libertades individuales... En verdad desde esos tiempos el Partido Socialista se había ido inclinando hacia la extrema izquierda.

El triunfo de un Allende que se declarase marxista, pero que afirmara que haría un gobierno democrático podia ser aceptado por un chileno mas bien tolerante.

El Diario Ilustrado (de tendencia conservadora) publicaba antes de las elecciones: "Es indudable que no queremos para Chile lo que el Frente Popular trajo a España: templos incendiados, conventos profanados, religiosas violadas".

Con ese clima se desarrollaron las elecciones presidenciales del 4 de Septiembre de 1970.

Allende triunfó en las urnas con 1.075.616 votos (el 36,3%). Segundo, resulto Jorge Alessandri con 1.036.278 votos (34,9%) y tercero, Tomic con 824.849 votos (27,8%).

Allende era virtual ganador aunque con una estrechísima primera mayoría relativa. Le ganaba a Alessandri por apenas 39.000 votos (el 1,4%).

El resultado revelaba también que casi los 2/3 del electorado rechazaba una alternativa marxista. Los que votaron por Alessandri y por Tomic (2 de cada 3 chilenos) creían en la democracia.

El proceso electoral todavía no había terminado la Constitución chilena establecía que quedaba ungido como Presidente electo el ciudadano que obtuviera la mitad +1 de los votos. A Allende le faltaba muchísimo: 400.000 votos (el 15,2 %).

Cuando no existe tal mayoría, la Constitución indica el camino: el Congreso pleno (50 Senadores y 150 diputados) tendrá que elegir entre las dos primeras mayorías. En este caso, tenía que ser entre Allende y Alessandri.

Ambos ante el Congreso pleno llegaban en igualdad de condiciones. La Democracia Cristiana durante la campaña electoral había propuesto crear la segunda vuelta, como en Francia. De este modo el Presidente elegido representaría a las grandes mayorías. Sin embargo ni los partidarios de Alessandri ni los de Allende aceptaron esa iniciativa.

De ahí que quedara sobre el Congreso la trascendental responsabilidad de dirimir el pleito.

Existía una tradición que para los chilenos pesaba mucho. Hasta entonces siempre el Congreso pleno había respetado la primera mayoría. Incluso durante la campaña los tres candidatos repitieron "el que gane por un voto será el presidente".

Ahora venía el dramático dilema. Los que votaron por Alessandri argumentaron: es cierto que existe esa traición pero fue entre candidatos democráticos; ahora es abrirle las puertas de la moneda al marxismo, siendo una minoría.

En el Congreso pleno Allende era también una minoría. Contaba apenas con 78 parlamentarios. Mucho menos de la mitad. Si Allende esperaba ser Presidente, necesariamente debía golpear las puertas de la Democracia Cristiana. Ella con sus 75 parlamentarios decidía.

Pero la Unidad Popular despertaba recelos. Allende estaba acompañado de algunos personajes no deseables. ¿Quién podría garantizar que no ocurriera con él lo mismo que sucedió con Fidel Castro, que en Sierra Maestra se proclamaba demócrata, católico y devoto de la virgen ?

En una dramática reunion, la Junta Nacional de la Democracia Cristiana acordó con sus parlamentarios que le darían el voto a Allende en el Congreso pleno, pero siempre que aceptara el cumplimiento de 7 Estatutos de Garantías Democráticas, las cuales serian incorporadas en la Constitución.

Las 7 garantias eran:

- La Constitución aseguraba la libre creación, existencia y desenvolvimiento de los partidos politicos

- Libre acceso a la prensa, radio y television de todas las corrientes en igualdad de condiciones.

- Constitucionalmente se consagraba que la fuerza publica estaría compuesta exclusivamente por las Fuerzas Armadas y Carabineros, y que no se podrían organizar ni milicias populares ni guardias.

- Las Fuerzas Armadas y Carabineros serian instituciones profesionalizadas, jerarquizadas, obedientes y no deliberantes. Se reservaba a los Comandantes en Jefe la facultad plena para el nombramiento de sus subordinados.

- En el Estatuto de Educación se proclamaba que esta seria independiente de toda orientación ideológica oficial.

- Se reiteraba la garantía constitucional que establece el derecho a asociarse, a través de cooperativas o sindicatos, y que se mantendría el derecho a huelga.

- Se modernizaban las garantías constitucionales del derecho de reunion y de libertad personal.

Por primera vez se manifestaba desconfianza hacia quien seria elegido Presidente de la República.

El Congreso pleno finalmente eligió a Allende Presidente de Chile con 2 tercios de los parlamentarios: 153 votos contra 35 de Alessandri y 7 en blanco. Así es como la Democracia Cristiana le permitió a Allende llegar a la presidencia de Chile.

**********************************************************************************

Información basada principalmente en la obra de Hernan Millas y Emilio Filippi "Anatomía de un Fracaso".

Hernán Millas nació el 5 de mayo de 1921, y estudió un año de Leyes en la Universidad de Chile, para después dedicarse al periodismo. Trabajó como reportero y columnista en los diarios El Clarín y La Época, en las revistas Ercilla y Hoy, y en la radio Santiago. También escribió varios libros. Y en 1985 recibió el Premio Nacional de Periodismo.

Emilio Filippi, Profesor universitario recibió el Premio Nacional de Periodismo en 1972 con mención en redacción. Inició su vida en el periodismo en 1942 trabajando en el diario “La voz de la columna’’ de Villa Alemana del cual llegó ser su director. En 1965, se incorporó como gerente de publicaciones periodísticas de Zig-Zag.

Fue director de la revista Ercilla entre 1968 y 1976. Fue el fundador y director de la revista “Hoy’’ y del diario “La Época’’ (1987), que dirigió hasta 1993. Mismo año que fue embajador de Chile en Portugal, nombrado por el Presidente Patricio Aylwin.